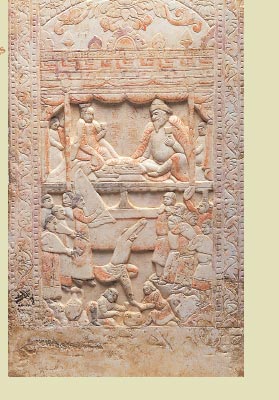

The Sogdians, an Iranian people who emerged from Central Asia, were instrumental in trade along the Silk Routes. They expanded their colonies deep within the Chinese continent and dedicated their lives to commerce. In the burial system of the Northern dynasty, the stone couches would not soil the sacred fire, water, and earth. The Sogdians carved their tales of reaching paradise, where festive banquets, filled with Central Asian music and dance, were held.

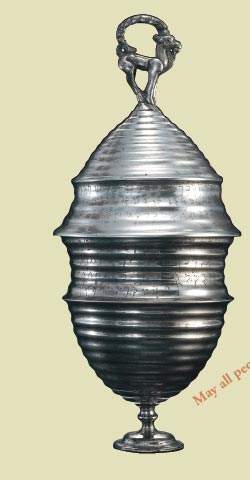

After the eastern expedition of Alexander the Great, Hellenistic images of paradise took root in Central Asia and northwest India. This reliquary, which combines the two Gandharan wine cups, perhaps reflects this tradition. In a kind of prohibition proclamation by Scythian princes, who were Buddhists, inscribed here are the words, “Dedicate this in a stupa so that all people can attain eternal peace.”

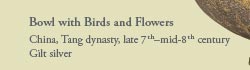

The Central Asian silverware introduced by the Sogdians became refined objects of beauty in Tang China. This silver bowl, at a glance, appears to be a Central Asian copy, though the sacred trees of West Asia are here paired with swallows and wild geese instead of sheep and goats. Though geese disappear in the spring and sparrows appear, both announce the arrival of this season. Carved here are the poetic sentiments of Tang dynasty.

Emperor Wu of Han, who was concerned over the invasion of China’s northern edges by nomads, sought the heavenly horses of Central Asia. These pedigreed Persian horses of Nisaia were renowned throughout the region. Envoys, carrying large sums of money and golden horses, visited many times and finally, after many difficult voyages, acquired several dozen of these sacred horses.

This gold figurine was created on the Silk Routes, which connected East and West, and perhaps played a role in opening its doors.

This gold figurine was created on the Silk Routes, which connected East and West, and perhaps played a role in opening its doors.

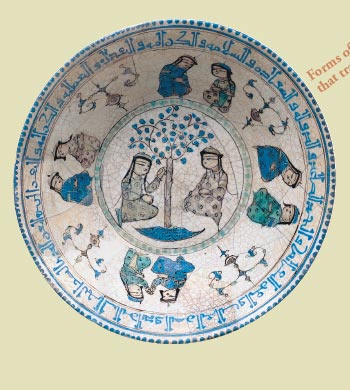

Teachers of Islam taught Sufism, the mysticism that adopted the complex ancient spiritual world of West Asia. The image of a sacred tree, which formed ancient Iranian mythology and sprung from the sacred sea, appears on the surface of this ceramic bowl, which corresponds to Sasanian silverware. The motif here transcends time and religion and within it lies the deep wish to attain a live, eternal paradise.

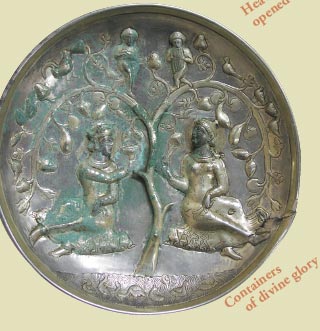

The Sassanid Persia, which rose from southern Iran, sought to revive the influence of ancient Persia, which had been subjugated by the Greeks and nomadic tribes. The myths of ancient Iran and the glory of the Zoroastrian gods bestowed on the kings adorned the gifts of silverware that were presented to honored guests. This custom of giving silverware was also transmitted to China via the Silk Routes.

Organized by MIHO MUSEUM and The Kyoto Shimbun Co., Ltd.

In cooperation with Shiga Prefecture, Shiga Prefectural Board of Education, NHK Otsu,

Biwako Broadcasting Co., Ltd., and FM Kyoto Inc.

In cooperation with Shiga Prefecture, Shiga Prefectural Board of Education, NHK Otsu,

Biwako Broadcasting Co., Ltd., and FM Kyoto Inc.