Glass, which was first produced in northern

Mesopotamia about 4500 years ago, continues to mesmerize people with

its brilliant colors and exquisite radiance to this day. Ancient

Mesopotamian documents, recorded on clay tablets and ancient

Egyptian texts, reveal that glass techniques evolved over time, due

to demand for precious stones such as the sacred blue lapis lazuli.

Various colored glasses came into creation, later, from about 3500 years ago, when glass vessels began to be produced. Glass reproduced the azure blue of lapis lazuli, the blue-green of turquoise, the deep red of carnelian, and purple of amethyst. Production techniques eventually increased in sophistication to surpass natural semiprecious stones in beauty, such as seen in mosaic glass and gold sandwich glass.

This exhibition presents approximately two hundred glass objects, featuring ten internationally acclaimed works of ancient glass from the British Museum (eight of which will be shown in Japan for the first time), together with outstanding works from Japanese collections. The exhibition begins with an introduction of colors and techniques, followed by a comparison of ancient works to semiprecious stones and contemporary reproductions, and concluding with an exploration of the mysteries of glass based on the results from scientific analysis. We hope museum visitors will enjoy the ancient sensibilities that created a new aesthetic realm and skillfully employed the transparent quality and free-flowing forms of glass in an age when it was considered as valuable as semiprecious stones.

Various colored glasses came into creation, later, from about 3500 years ago, when glass vessels began to be produced. Glass reproduced the azure blue of lapis lazuli, the blue-green of turquoise, the deep red of carnelian, and purple of amethyst. Production techniques eventually increased in sophistication to surpass natural semiprecious stones in beauty, such as seen in mosaic glass and gold sandwich glass.

This exhibition presents approximately two hundred glass objects, featuring ten internationally acclaimed works of ancient glass from the British Museum (eight of which will be shown in Japan for the first time), together with outstanding works from Japanese collections. The exhibition begins with an introduction of colors and techniques, followed by a comparison of ancient works to semiprecious stones and contemporary reproductions, and concluding with an exploration of the mysteries of glass based on the results from scientific analysis. We hope museum visitors will enjoy the ancient sensibilities that created a new aesthetic realm and skillfully employed the transparent quality and free-flowing forms of glass in an age when it was considered as valuable as semiprecious stones.

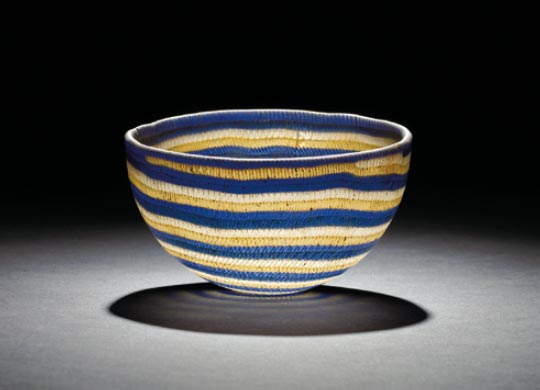

Spiral Lace Bowl

Eastern Mediterranean region (said to be from Crete),

2nd century B.C.

The British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Eastern Mediterranean region (said to be from Crete),

2nd century B.C.

The British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

As its name suggests, this bowl has a spiral motif but not

just spirals. Four-colored threads or strands encircle the

vessel to create a stunning lace glass bowl. The colors

include navy, blue, yellow, and white, which were in vogue

in the Mediterranean before the Common Era and which were

covered with a colorless, transparent glass layer. It

appears that the glassmaker used the core-forming technique,

in which a clay mold with a rod affixed to it was made to

shape the core of the bowl that was then coated with molten

glass. The colored strands were accurately applied by

trailing them around the vessel. Creating the glasswork

while heating the glass is extremely difficult and requires

the utmost precision. This precursor of Venetian lace glass

was produced long before the brilliance of Venice though its

radiance has not waned in the least.

Head of a Pharaoh, possibly Amenhotep III

Egypt, 1400–1363 B.C.

MIHO Museum

Egypt, 1400–1363 B.C.

MIHO Museum

King Amenhotep III (r. circa 1390–1352 BCE), the grandfather of

King Tut and father of King Akhenaten, was the pharaoh of Egypt’s

eighteenth dynasty. As the king of a golden age, Amenhotep III was

known for having constructed a colossal artificial lake, adjacent to

his royal palace, and temples throughout Egypt. Given the royal

family’s monopoly over the secret technique used to produce “gem,”

at the time, it is no surprise that remains of a glass workshop was

discovered at the site of Amenhotep III’s palace.

This life-sized work is the greatest existing ancient Egyptian glass carving, which demonstrates excellent workmanship. To imitate the extremely precious blue gemstone, lapis lazuli, cobalt found in the western deserts and bronze were mixed to create a deep blue color, and an opalescent agent made of antimony as its primary material was used to produce its opaque, weighty quality. The eyes consist of inlaid black glass and white stone. Highly skilled technicians, who served the pharaoh, under the great patronage of the royal family, the finest materials, and immense effort made this masterpiece possible. Perhaps it was the portrait of a god king holding a blue glass head or a carving of a head, which was placed on a funerary coffin.

This life-sized work is the greatest existing ancient Egyptian glass carving, which demonstrates excellent workmanship. To imitate the extremely precious blue gemstone, lapis lazuli, cobalt found in the western deserts and bronze were mixed to create a deep blue color, and an opalescent agent made of antimony as its primary material was used to produce its opaque, weighty quality. The eyes consist of inlaid black glass and white stone. Highly skilled technicians, who served the pharaoh, under the great patronage of the royal family, the finest materials, and immense effort made this masterpiece possible. Perhaps it was the portrait of a god king holding a blue glass head or a carving of a head, which was placed on a funerary coffin.

|

|